By Caroline Visser, Founding Partner & Managing Director, Global Road Links

Over the last few years, an increasing number of electric mobility initiatives and services have emerged in Sub-Saharan Africa. It was immediately evident that the development of e-mobility on the continent would follow a different path than in the developed world. Where in the developed world e-mobility is introduced through the high-end, private and mass-produced vehicle markets, in Africa it is the informal and public transport sector championing the introduction of electric vehicles and mobility services. So, we decided to explore these trends and differences, and what has been written about them, in this blogpost. [1]

The role of transport in climate change and air pollution in Africa

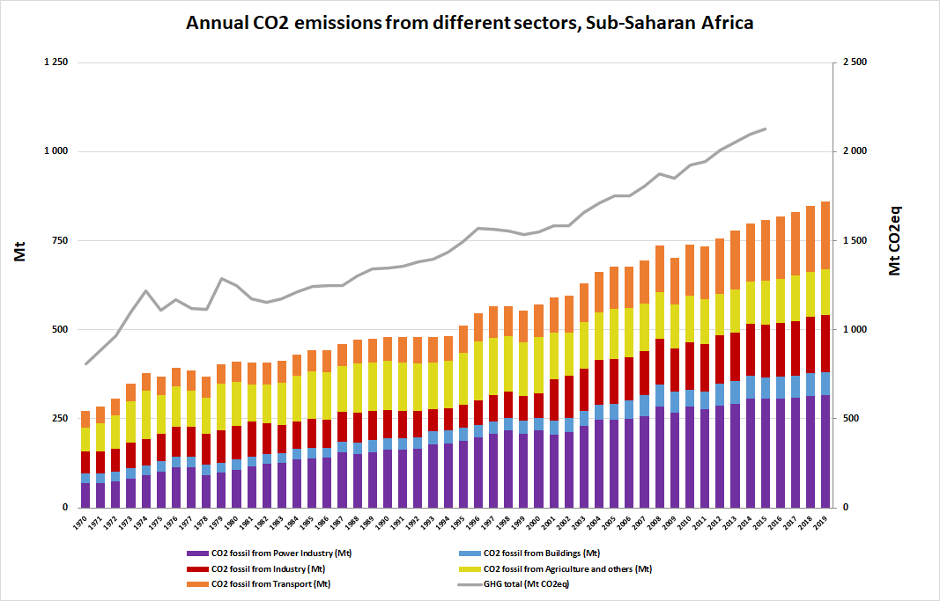

Data compiled by the Joint Research Centre of the European Commission show a clear upward trend of Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions since the 1970s. [2] As displayed in the chart below, the largest share of emissions in 2019, about 37%, comes from power generation (depicted in purple). However, it is clear that transport’s share has increased over time as well. In 2019 it stood at 27% of total CO2-emissions.

The overall image on air pollution in Sub-Saharan Africa is not a positive one. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), the number of air pollution deaths per 100’000 inhabitants is approximately 200 (2016 data) in Sub-Saharan Africa. [3] This is much above the world average of around 110 for the same year. Some negative extremes, such as Sierra Leone and Nigeria, reached over 300 deaths per 100’000 inhabitants. However, the WHO data does not specify the source of the air pollution.

Reliable air quality data on city level in Sub-Saharan Africa, and in particular on transportation as a source of air pollution, is scarce. Researchers of the University of Birmingham have attempted to map transport related air pollution in a number of East-African cities (i.e. Kampala in Uganda, Nairobi in Kenya and Addis Ababa in Ethiopia). None of the three cities in the study met with the WHO air quality standards. All three cities were in a near-permanent state of PM2.5 levels that were unhealthy for sensitive groups and, at moments, for all. The highest peaks were observed in Kampala. The study concluded that “roads and traffic need to be a focus for mitigation strategies to reduce air pollution exposure”. [4]

Electric mobility as part of the solution

Electric mobility can be regarded as part of a broader set of measures to transform and decarbonize the transport sector. A (non-exhaustive) summary of environmental impacts, based on the current state of the art in research and cost-benefit comparisons between electric vehicles and combustion vehicles (based on passenger/light duty vehicle). [5]

In terms of climate change impacts, the life-cycle GHG emissions for an electric vehicle (EV) is higher than internal combustion vehicles in the raw material extraction and production phase. However, this is more than compensated by lower emissions during the use phase. It needs to be observed though that the source of energy used for charging EVs is an important determining factor is. Countries depending more heavily on coal or fossil fuels for their power supply will see less beneficial impacts than countries that rely on a more diversified and green power supply.

In terms of health impacts, electric mobility provides a clear benefit related to decreasing urban air pollution, although this is more nuanced than some would make you believe. There are, for instance, uncertainties related to non-exhaust particle matter, and the location of power generation in or around an urban area also plays an important role.

Other health aspects relate to noise, human toxicity and traffic accidents. The reduction of traffic noise can be achieved at low speeds (< 50km/h) if a substantial share of the traffic (25% upwards) are electric vehicles. Human toxicity impacts of EVs are limited in comparison with climate change impacts, but generally higher than combustion engines. And research has shown electric driving can contribute to a reduction of traffic accidents.

Electric mobility does not just constitute the introduction of new technology; it is a disruption of current systems.

However, it would be unwise to think that electric mobility just constitutes the introduction of a new technology. In fact, it is a disruption of current systems which relate to: the extraction of raw materials for battery production and wiring; vehicle and battery standards, certification; establishment and operation of charging infrastructure; changes to vehicle supply chains, business models and skills needed; increase in electricity demand and the need for a stable supply of (preferably renewable) power; public budget implications (taxes, subsidies); and end-of-life considerations (recycle or dispose?).

Specifics of Sub-Sahara Africa

Collet et al (2021) have summarized the challenges for electric mobility in the Sub-Saharan African context. [6] These include:

- Mobility patterns: the majority of trips in SSA are undertaken using informal transport services.

- Vehicle ownership: vehicle standards and certification are often lacking or not regularly enforced and the vehicle park exists largely of imported, pre-owned vehicles.

- Lower availability of capital: determining the pace of vehicle stock turnover and the ability to invest in charging infrastructure.

- Power sector generally generates insufficient power and the grids are unreliable.

- The introduction of electric mobility presents budget challenges for countries depending on revenues related to fuel use (e.g. fuel levies/taxes).

Collet et al also listed a number of benefits, including the environmental ones already addressed above. Increased power demand can lead to increased revenues. Furthermore, there are economic benefits in terms of lower vehicle operating costs and job creation through local vehicle manufacturing or assembly. Additionally, some countries can have budget benefits through the reduction of fuel subsidies, which opens up alternative spending opportunities for tax money.

A quick scan of e-mobility initiatives that have emerged over the past few years in countries like Rwanda, Nigeria, Uganda and Kenya, show that many of them focus on the informal/public transport sector, like motorcycle taxis or minibuses for public transport. Many businesses in the sector adopt a Mobility-as-a-Service (MaaS) concept; the user purchases the vehicle, but special arrangements are in place for the battery. Generally, a battery-swap service is provided with the vehicle, leaving charging with the companies giving out the batteries. Assembly of vehicles mostly takes place in-country, with components being imported from more mature markets like China and Europe.

The role of governments varies widely, from actively supporting e-mobility businesses and users (Rwanda), to participation in an electric vehicle manufacturing company (Uganda), to leaving the initiative to the market.

Recommendations for stimulating electric mobility

A number of recommendations can be formulated for authorities wishing to stimulate the uptake of electric mobility in their jurisdiction. But first of all, it is important to realize that it includes dealing with uncertainty, as the oil price, electricity prices, battery costs and performance and mobility patterns change over time. Nonetheless, some general lessons can be drawn:

- Embedding the transition towards electric mobility in national environmental strategic objectives and policies, linked to energy transition away from fossil fuels, seems more effective than a siloed policy approach.

- Collaboration between the transport and power sector is needed to prevent uncontrolled charging and to explore innovative solutions including stationary electricity storage and vehicle-to-grid technologies.

- Vehicle regulations and standards need enhancing and enforcing.

- There are different ways to incentivize the uptake of electric mobility. One of them is through the stimulation and support of the innovative powers of the private sector, e.g. by creating demand through public tenders. Carrots and sticks in terms of taxation, carbon pricing and subsidies can play a role. And public-private partnership options can be explored to reach both positive socio-economic as well as investment returns.

- International collaboration might be useful to exchange experience and knowledge, research outcomes and to pool standardization efforts.

Want to know more?

Global Road Links has the expertise to support road authorities with the development and implementation of their electric mobility strategy, incentivization packages and exploring public-private partnership options. Furthermore, we provide support services for electric mobility start-ups with the modelling of their business case and cost-benefit analysis for presentation to investors and potential customers.

Contact us through info@globalroadlinks.com to start the dialogue!

References:

[1] Caroline Visser has presented the topic at the 2nd International Congress on Transport Sector Development on 15 December 2021. This blogpost is based on the presentation that was given.

[2] Crippa, M. et al. (2019, 2020). Fossil CO2 and GHG emissions of all world countries. 2019 & 2020 Report. Joint Research Centre, European Commission.

[3] World Health Organisation (2016).

[4] Singh, A, Ng’ang’a, D, Gatari, M, Kidane, AW, Alemu, Z, Derrick, N, Webster, MJ, Bartington, S, Thomas, N, Avis, WR & Pope, F (2021). Air quality assessment in three East African cities using calibrated low-cost sensors with a focus on road-based hotspots Environmetal Research Communication, Vol 3, no. 7, 075007.

[5] European Environment Agency (2018). Electric vehicles from life cycle and circular economy perspectives. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

[6] Collet, et al (2021). Can electric vehicles be good for Sub-Saharan Africa? In: Energy Strategy Reviews 38, paper 100722. Elsevier.